- Baltimore Orioles catcher Maverick Handley advises young athletes to embrace the team aspect of sports.

- Handley emphasizes that burnout is real and it is acceptable for athletes to take breaks.

- Handley encourages players to communicate their struggles and seek help, stating it is a sign of maturity.

We tend to think of getting drafted by a major league sports team as a glamorous endeavor.

Sports was never the solution to his problems. It was more like a tonic to help combat them.

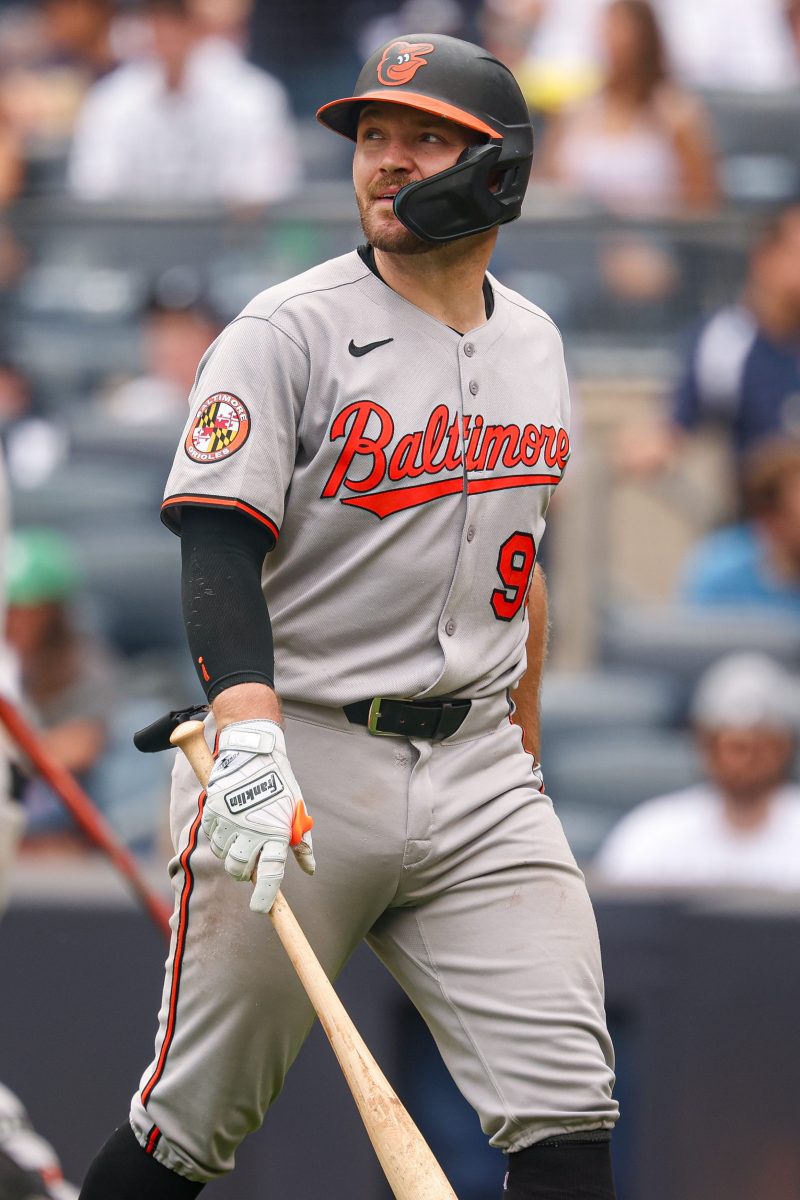

“I recently went through my kindergarten, preschool reports that the teachers would send to my parents,” said Handley, a 27-year-old catcher the Baltimore Orioles drafted in 2019. “I read through them, and it said, ‘Your child is extremely competitive, everything’s competition,’ and my parents were like, ‘We know. We’re working on it. This is kind of how he’s wired.’”

Handley started T-ball at age 3. He played football, basketball and, growing up in Colorado, skied until he was 12 and took a nasty fall.

He learned spills like that come at you as you get older, in and out of sports. Travel baseball became so intense at age 14 he wanted to quit. Then came the low minor leagues, where everyone else is really good and Handley said it felt like every man for himself.

When he felt alone, he could go back to what was familiar – his family, his routine, his difficult experiences endured with teammates and classmates – for help and comfort.

“You are going to struggle,” he told a group of youth and high school baseball players last month. “Talk about it. At Stanford, we had a term called ‘duck syndrome.’ From the outside, everything looks calm and smooth — like a duck gliding on the water.

“But underneath, the duck is paddling like crazy. College is hard. Baseball is hard. Life is hard. Everyone struggles. Communicate when you do. There are resources and people who want to help you.

“Reaching out is not weakness. It’s maturity.”

Handley was the guest speaker at an event hosted by my son’s travel team for high school seniors who had committed to play the sport in college. He offered them tips on what to expect within intercollegiate athletics. I caught up with him afterward to talk about how his experiences and advice can help all young athletes:

It’s not as much fun to play for yourself. Embrace the team aspect of sports.

Handley constantly needed to be doing something. His parents, Jill and Jeff, threw him into sports.

Maverick joined a serious club baseball program at 12, and it enveloped him. His parents couldn’t afford it, so they picked up shifts in a bingo hall the team owned. Their son got a scholarship to play on the team.

It was an early lesson he got about being a part of something larger than himself. He felt it again when he debuted in the major leagues on April 29, 2025, after more than seven seasons in the minors.

He and everyone around him, it seemed, were just trying to contribute positively in any way they could for a win.

“The big leagues is great,” Handley says. “That’s the best baseball and the best feeling of winning with a team, especially when you’re playing against guys who are also so talented.

“There’s been much more self-doubt in pro ball than there was in high school or college. I think what I really enjoyed about high school and college is the feeling of a team and feeling like you’re really playing for the guys around you. If you don’t play well, but you guys still win, there’s still, like, a sense of victory.

“And in pro ball, sometimes it can feel a little bit different because if you do really well, your team loses, it can sometimes be a better thing because it says you’re ready to move on to the next level, especially if you’re the only one succeeding. So, it feels like sometimes you’re not really playing to win, you’re just playing for yourself, which can be difficult, not as fun.”

Handley had been there before, and he leaned on that experience.

Burnout is real. It’s OK to take a break.

When he was 14, Handley was at a wood bat tournament. It was one of the first times he really struggled.

“I just sucked,” he says. “I was terrible, my confidence was down. And in that pain, I was like, ‘I don’t want to keep playing.’”

Jill and Jeff told him they wouldn’t force him to play baseball. Instead, their son says, they allowed him to take off the rest of the summer season (about a month). He played fall and winter sports and was back on the diamond in the spring, feeling recharged.

“They kind of sympathized,” he said, “They were like, ‘OK, we hear you, we’re gonna make a change.’ It allowed me to kind of come back to the sport.”

To this day, when he and his wife go on a vacation after the season, he takes two weeks completely off where, “I just try not to even think about baseball.”

There are no shortcuts: ‘How you do one thing is how you do everything’

Handley’s father had to pay his own way through Vanderbilt, and the expectation was the same for his son.

Jeff Handley had played football in high school, and realized the value of sports, but his son wasn’t allowed to play if his grades lagged behind. The expectation was to get A’s, and Maverick missed practice at times to catch up on homework.

“It was very clear,” Maverick said, “‘I’m gonna help you get as many scholarships, and I wanna make sure you take APs, and I’m gonna make sure that you are in the best situation going into college, but I’m not paying for your college.’ So I think that he motivated me to do well in school so that I would get more money, more opportunity in college, not have to bear the burden of debt.

“I definitely felt overwhelmed at times. I’m not proud to admit it, but I cheated once or twice in high school to make sure I got a good grade. I’m not super proud about it, but it is a reality. I knew that I had to get an A. But, for the most part, I succeeded pretty well and kept up with my work and spent a lot of time on it.”

He said cheating didn’t feel good, and he only did it once or twice, the guilt overcoming him.

“I think it was, like, a pointless quiz that really wouldn’t have impacted my grade if I had struggled, but I felt that pressure of not being allowed to struggle in a sense, and so I cheated.

“In college, you couldn’t cheat on the test. Either you knew it or you didn’t.”

As we grow as athletes and people, we watch those who are successful around us and feed off of them. The best piece of advice Handley gleaned from watching professional players: How you do one thing is how you do everything.

We can be as intentional about how we stretch and take care of our bodies as how we present ourselves as students in class. If we get into a routine with our lives, we find comfort and satisfaction in it, and we show others how relentless we can be, no matter what the results.

“Part of what makes Stanford athletics great is we are willing to adjust to the kid as much as we can. We understand what an unbelievable opportunity it is for these kids to go to school,” then-Cardinal assistant coach Jack Marder told the Associated Press for a 2019 profile about Handley. “If he’s trying to be an orthopedic surgeon and we’re going to get in the way of that so he can make baseball practice, to me that’s ridiculous, so we’re going to find a way, any way we can, to still develop him as a player with allowing him to do what he needs to do from the academic side of it. My obligation is just to be available to him.”

Find your edge and take advantage of your opportunity

Stanford discovered Handley when a scout was at a game during his junior year of high school to check out Bo Weiss, a pitcher and the son of former major leaguer and current Atlanta Braves manager Walt Weiss.

Handley was catching for Weiss and had a big day. He had good grades, and his dad had forced him to start taking standardized tests as a freshman.

“The (Stanford) coach followed up with my club ball coach and was able to show I got like a 30 on the ACT as a sophomore,” he said. “And so they were very interested at that point. If I was an even talent with some other catchers, I had the academic benefit. I’m a believer that if you take care of your grades, that kind of communicates to the coach that he doesn’t have to worry about you off the field, especially in college.”

When we get to a college, or even a high school team, we can easily be humbled. We’re sometimes not one of the top players, and we sit on the bench for long periods of time. When that happens, though, we observe everything and learn.

Support your teammates who are playing, which college coaches love.

Your older teammates, Handley said, likely were in your exact position not long ago. Ask them what they did and what worked: “Then don’t just copy them — do it better.”

At Stanford, Handley says he was the bullpen catcher for 23 of the first 24 games of a season.

“I thought I was better than the guys ahead of me, but they were older and had earned the coach’s trust,” he said.

Then, in one weekend, he played well as an injury replacement. He caught the next 34 games in a row.

All we can really control, Handley has learned, is our attitude and our effort.

“Don’t pout if you’re not playing,” he told the group assembled for my son’s awards banquet. “If you show how upset you are on the bench, all you’re doing is annoying the coach — and your opportunities will disappear.

“My coach used to say, ‘You are never that locked into a starting position … and you are never that far away from one.’”

Make sure your identity is not tied to your performance

If you play baseball, you know you fail much more than you succeed. The feeling can be all-consuming when you’re away from home and in direct competition for promotions.

“When your identity is rooted in your performance, it can lead to a lot of insecurity,” Handley says. “So making sure you’re filled up by something outside of your performance, I think, is really important.”

Handley likes to have a physical hobby, a creative hobby and what he calls a mental hobby. He goes to church, he does volunteer work, he reads and he plays chess, where, he says, there’s a huge underground dynamic in professional baseball.

He finished his bioengineering degree from Stanford in March 2021, completing it online during spring training. He is open to various possibilities when he’s done playing.

“I can realistically say I think I have 3 to 8 years left in the game,” he said. “I had two great roads of professional baseball and then medical school. And now I’m several years removed from school and I’d have to take my MCAT, I’d have to go work in some labs. And so just to even get back into med school would be a multi-year process. And I’m married. I want to start a family. And so those goals and priorities have kind of changed in a sense.”

He thinks about going to school to become a physician’s assistant, or to law school, to go into coaching as a volunteer in college, where he could get a master’s degree.

Whatever he does, he knows he has a circle – his wife (Abby), his parents, his older sister (Sydney) and younger brother (Knox) – that has been a crucial part of his support system.

“When it’s time to hang up the cleats, make sure you got everything you could out of it,” he told the group of college baseball commits at the banquet. “And one last thing: Don’t forget to call your mom.”

Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for two high schoolers. His Coach Steve column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.